Pedagogical Connections to Classical Thinkers

The philosophies of classical thinkers have influenced many of our modern philosophies on education. By examining writings of Plato and Aristotle, one can reflect on their own ethics and make connections to the moral fabric of past pedagogues. Over the past two thousand years many theorists have contemplated how to improve moral education and academic achievement. They have read and reflected on the philosophies of the ancient Greeks. This contemplation will be ongoing into our futures, as our societies and cultures continue to evolve. Knowledge is never static therefore today’s teachers must continue this philosophical contemplation. When examining the past, it is also important to realize that new philosophies develop based on modern interpretations of old observations. Therefore, those that teach must continuously learn and reflect on new knowledge in order to provide a good education to students.

Interpretation of Writings by Plato and Aristotle

When reading Plato’s Cave: On Breaking the Chains of Ignorance, it is clear that Plato’s ancient text still holds relevance today. This allegory shows prisoners chained underground in a cave. They cannot move their heads therefore the only sights they are able to witness are shadows cast on the blank wall in front of them, illuminated by the fire behind them. While they can hear the noises of puppeteers and passersby, they cannot see these people. They can only see their shadows cast on the wall. The prisoners accept their chains because when they try to move their heads, the light from the fire is dazzling and painful. They would rather bare their chains of ignorance than be exposed to the light of this new knowledge. In Nicomachean Ethics, Book I, Aristotle also expresses that vulgar men choose to live only seeking pleasure and enjoyment, in other words ignorance presents itself as bliss. As portrayed in Plato’s cave, one prisoner who was originally reluctant to leave his shackles is dragged out of the cave against his will. He begins to see the outside world as it is. Over time, his eyes adjust and he can see the sun.

The writings of these two philosophers hold relevance today. For example, many students may be persuaded to join the military when they graduate from high school. Recruiters might present them with literature promoting the benefits of this investment and the pride that comes with serving their nation. A military career will also provide them with many opportunities, such as obtaining college financing, world travel, hands-on training in a variety of fields, and medical insurance for themselves and their families. In Nicomachean Ethics, Book I, Aristotle states “it frequently occurs that good things have harmful consequences: people have before now been ruined by wealth, and in other cases courage has cost men their lives.” Students who join the military may not be aware of the risks associated with military training, deployment, and war. They could find resources to further information and examine benefits and consequences of making this career choice. It is important for teachers to realize that many students will not look for these resources. Teachers must understand that our students may be like the prisoner in the cave; students need to be led to the sources of knowledge in order to make educated decisions. Otherwise, they may be exposed to harmful, unknown consequences of a “good thing”.

Furthermore, in order to effectively teach students and lead them to accurate information, teachers should increase their own knowledge and academic growth throughout their careers. Aristotle also states in Nicomachean Ethics, Book I:

To criticize a particular subject…a man must have been trained in that subject: to be a good critic generally, he must have had an all-round education. Hence the young are not fit to be students of Political Science. For they have no experience of life and conduct, and it is these that supply the premises and subject matter of this branch of philosophy. And moreover they are led by their feelings; so that they will study the subject to no purpose or advantage, since the end of this science is not knowledge but action.

Teachers should know the subject matter they teach and stay current on pedagogical methods and styles. In a career of education, it is logical that the educator be educated. Plato and Aristotle argue that if we do not search for new knowledge, we are also bearing the chains of ignorance. This necessity to be academic throughout one’s teaching career requires additional flexibility and examination of one’s personal and pedagogical philosophies.

More Recent Applications of Classical Philosophies

When examining the writings of classical thinkers it is useful to analyze the pedagogical philosophies of those before us. Exploration of the writings of various historic figures such as Plutarch, Martin Luther, and Leo Tolstoy provides examples of how the ideas of the Greek philosophers have been examined and interpreted over time. Plutarch expresses the celebration of Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato by all mankind in The Education of Children. Martin Luther conveys the importance of learning about the classical era and understanding the past in order to avoid that which-is harmful in his Letter in Behalf of Christian Schools. Tolstoy observes the use of classical and biblical philosophy and their connections with the school of his day in On Popular Education from Yasnaya Polyana. As pedagogical methods have evolved, the philosophies of the Greeks are still continuously interpreted to support the arguments of modern theorists. Stearns (2011) states, “…the classical period gains significance in world history from the fact that each key regional civilization established a number of lasting features…which can still be identified today” (p. 30). Historic and modern thinkers can easily examine and find relevance to the philosophies of the classical time period and choose to agree or disagree with them.

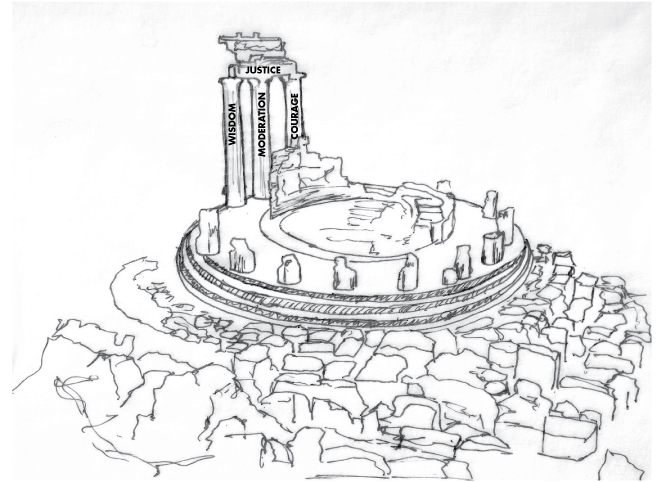

One example of a modern application of classical philosophy is observed when examining Plato’s three values, wisdom, moderation, and courage. The Greeks understood this concept as the balanced life (Scheuerman, 2014). As represented by the illustration of Tholos in Figure one, these three values form the structural supports of the stones above. If one of these three values is missing, the structural column will disappear and justice will fall. If these values are not balanced, in other words, if one is courageous to the point of foolishness, justice also cannot prevail. This balance can also be compared to situations in modern education. For example, in a school, an administrator may manage a budget to facilitate that the financial needs of a school district or school are met. He or she may exhibit courage when communicating budget allowances to stakeholders within the school and local community, use moderation when balancing budgets for resources such as new technology, athletics, or special education, and utilize wisdom to ensure that the resources are utilized as efficiently as possible. If any of these values are weighted unequally, it is likely that this administrator may make unjust decisions.

The Source of Individual Philosophies

While many of the philosophies of classical thinkers can provide usefulness today, we should also understand the context of the culture that they came from. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle have significantly influenced the practices of educators throughout history yet they also “…lived in a slave society…where each new generation within the leisure class had a claim on higher education because of membership in the class…[and] that education provided an entry into the ranks of the virtuous” (Finley, 1987). This was also a time of aristocratic rule, where politics were very important to the functioning of civilization and religion was polytheistic. Schlesinger (1998) states “it may seem more important to maintain a beneficial fiction than to keep history pure–especially when there is no such thing as pure history anyway” (p. 53). Much of the knowledge from this period is lost therefore the knowledge we obtain from the writings of previous pedagogues are interpretations of this era. This is yet another reason why teachers should continuously study their own philosophies during the course of a lifelong education. While the philosophies of those past may hold significance today, this information should be exhibited with tact, understanding that knowledge evolves and interpretations of the past evolve as well.

Figure two illustrates Plato’s three values again, using a different view of Tholos surrounded by its ruins. Much of the knowledge from classical times was destroyed or lost in the post-classical period, what little we have left has been translated and interpreted over a vast expanse of time. When reflecting on history, it is important that we observe that we are missing information and our philosophies must reflect this knowledge as new discoveries present themselves.

As time progresses, the stones and ruins of the past will continue to be uncovered revealing new truths; the future will also present new advancements in technology and wisdom leading to new philosophies. When examining new methods to improve education, teachers should be aware of the sources of information they are teaching from and continue to learn about that subject matter.

Conclusions

Plato and Aristotle’s philosophies come from a very different era of education. Much of the information from this time period is missing therefore the writings must be interpreted with modern philosophies. Based on the writing of pedagogues before us, it is useful to examine the interpretations of classical philosophical theorists. Plutarch, Martin Luther, and Leo Tolstoy utilized classical knowledge to support their own philosophies. Many universities and educational institutions embrace the teachings of a Socratic era although we will never truly comprehend this knowledge in its originality. By examining the works and interpretations of other thinkers, we can further understand and develop our own pedagogical philosophies. Ellis (n.d.) states, “No one philosophy is right for all people. …What is important is that you, as a future teacher, carefully examine [multiple] philosophies as you begin to define your own personal educational philosophy” (p. 5). Moreover by continuing to uncover the past, we can try to build upon the philosophies of the ancient Greeks as well.

Although the concepts presented by Plato and Aristotle are out of historic context, they also provide insight when developing one’s own pedagogical philosophies today. When reading Plato’s Cave: On Breaking the Chains of Ignorance and Nicomachean Ethics, Book I it is useful see the relevance these texts hold in today’s world. In a modern interpretation, these writers inform us of the importance of providing a well-rounded moral and academic education to our students. They also communicate that we must be well versed in existing and new knowledge. Therefore I can summarize that teachers must remain academic throughout their careers to facilitate they are prepared to provide new instruction to students as new information presents itself. Furthermore, by examining the teachings of Aristotle and Plato, teachers can build on their own philosophies, as many pedagogues refer to the writings of classical thinkers. It is unfortunate that much of the knowledge from this time is lost and therefore essential that material is referenced accurately and with truth. As knowledge continues to evolve, teachers must comprehend that they will continuously need to break the chains of ignorance.

References:

Ellis, A. (n.d.). Philosophical perspectives. Personal Collection of (Ellis, A.), Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, WA.

Finley, M. I. (1987). The use and abuse of history: From the myths of the Greeks to Lévi-Strauss, the past alive and the present illuminated. (Revised edition). New York: Penguin Books.

Stearns, P. N. (2011). World history: The basics. London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Scheuerman, R. (2014). Session 2: Paideia and panhellism: The Greek experience. Personal Collection of (Scheuerman, R.), Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, WA.

Schlesinger, A. M. (1998). The disuniting of America: Reflections on a multicultural society. (Revised and enlarged edition). New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company.